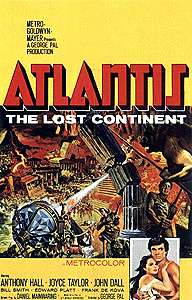

Atlantis, the Lost Continent (1961) -**

Atlantis, the Lost Continent (1961) -**

In 1961, the sword-and-sandal craze touched off by the success of Hercules/Le Fatiche di Ercole was reaching its peak. That year saw the release of four Hercules movies, five Maciste movies, and a handful of lesser offerings like The Mighty Ursus. These, of course, were all Italian films, but far be it from Hollywood to keep its hands off a lucrative trend. American competitors to the Italian imports began appearing as early as 1958, but as with their models, it wasn’t until the early 60’s that the genre really took root. The US studios also went about their sword-and-sandal adventure flicks a bit differently. While the Italians seemed to be forever searching for the biggest, most impressive retired bodybuilder available (whether or not he could act worth a damn), the Hollywood producers opted instead to structure their movies around what they knew best, and what they knew their poorer European rivals couldn’t possibly match: gaudy, expensive spectacle. What they did not bother with, as Atlantis, the Lost Continent makes abundantly clear, were stories that were any more sensible or actors who were any more talented than what the folks in Italy were coming up with at the time.

We’ll skip the “educational” pre-credits lecture from Captain Voiceover if that’s okay with you, and jump straight to Demetrios (Anthony Hall, aka Sal Ponti) and his dad, Petros (Wolfe Barzell, of Frankenstein’s Daughter and Homicidal), out on their fishing boat somewhere in the Aegean. They don’t seem to be catching a whole lot, but that’s about to become just about the last thing on the two men’s minds. In the distance, Demetrios notices a battered raft with a single, square sail, apparently adrift in the direction of the open Mediterranean. Swimming over to the raft, Demetrios finds it occupied by an unconscious young woman (Joyce Taylor, from Twice-Told Tales and 13 Frightened Girls). He and his father take that as their cue to call it a day as far as fishing is concerned, and head back to their village (which subsequent dialogue will suggest is located somewhere in Attica). When the girl from the raft awakens that night, she reveals herself as an extremely haughty, difficult, unpleasant person. There’s a very good reason for this, as a matter of fact, for Antillia (as she calls herself) claims to be a princess from a wealthy and faraway land, situated somewhere beyond the Pillars of Hercules— that is to say, out in the Atlantic Ocean. Neither Demetrios nor Petros believes her, for it is generally accepted throughout Greece that the Pillars of Hercules (the Straits of Gibraltar) mark the western end of the world, and that nothing but water and primordial chaos exist outside them. Nevertheless, both men are forced to agree that she must have come from somewhere, and her ignorance and bafflement in the face of local customs suggests that wherever that was is far away.

Antillia, understandably, can think of little other than getting back home. She doesn’t like the food or the clothes or the housing or much of anything else in Attica, but she obviously isn’t going to walk back to the Pillars of Hercules by herself. She’s going to need somebody to take her, and to that end, she begins working on Demetrios with all her power. She improvises makeup in an effort to make herself more beautiful. She hangs out at the shore when the boy is at work. She comes on to him with a brazenness that is absolutely unseemly in the royalty she claims to be. She name-drops her father, the king of Atlantis, and promises that vast wealth will be showered upon anyone brave enough to return her to him. Eventually, she gets the poor sap right where she wants him, but even then, she can’t quite seem to disguise her disgust at the idea of consorting with commoners, and she rebuffs the advances she has done so much to attract in the rudest possible manner. Naturally this means Demetrios is inoperably smitten with her. One night soon thereafter, Demetrios awakens to find Antillia’s bed empty. He catches up to her while she’s in the act of stealing his father’s boat (which she has no earthly clue how to sail properly), and in a spirit of generosity wholly undeserved by its recipient, offers her a bargain. He will sail her out to her fabled home in Atlantis, but he will spend no more than a month at sea. If there is still no sign of Atlantis after that, they will return to Attica, where Antillia will become the “dutiful wife” of Demetrios. She accepts the boy’s proposal.

As it happens, Demetrios and Antillia do indeed spend just about a month out at sea. Right as Demetrios is first raising the subject of turning the boat around, what looks for all the world like a great sea monster surfaces astern of them, but appearances here are deceiving. The big fish-like thing approaching the boat is no monster, but rather an Atlantian submarine! It pulls up alongside the fisherman’s boat, and disgorges its commander, Zaren (John Dall), and several soldiers. Zaren takes both Antillia and Demetrios aboard, submerges his vessel, and sets a course for Atlantis.

The reception is not quite what Demetrios expected. Sure, the Atlantians are perfectly happy to see their bitchy, spoiled, obnoxious princess, but Demetrios ends up as a slave in some kind of mining operation. The object of this venture, as fellow slave Xandros (Jay Novello, from The Mad Magician and the 1960 remake of The Lost World) explains, is the extraction from the earth of mysterious crystals that power Atlantis by harnessing the energy of the sun. The labor for the project is recruited much the same way Demetrios was— shipwrecked and storm-tossed sailors from every seafaring nation of the globe find their way to Atlantian shores and are snapped up by the Atlantian army. Most are simply put to work, but a few special unfortunates are handed over to a sadistic scientist (Berry Kroeger, of The Time Travelers and Nightmare in Wax), who transforms them into beast-men in a laboratory called the House of Fear. (One assumes that “House of Pain” is a registered trademark of Moreau Industries Ltd...)

While that’s going on, Antillia is getting a rude awakening of her own— though nowhere near as rude as her new Greek boyfriend’s. Her father, King Kronas (4D Man’s Edgar Stehli), has aged alarmingly in her absence, and has become almost too feeble to rule. Zaren has thus become the power behind the throne. This is bad news for Antillia, because she is betrothed to Zaren, but apparently doesn’t like him one little bit. She won’t be marrying Demetrios, however, for the boy has been sent back to his homeland— or so the king says. We, of course, know better, and so does Antillia after an indeterminate but obviously short amount of time. One afternoon, while she’s out riding with an entourage of bodyguards, her cavalcade crosses paths with a slave convoy, and who should be among the oppressed toilers but Demetrios. For the one and only time in the entire film, Demetrios gives Antillia the treatment she deserves, and lobs a mudball at her face when he sees her parading by on horseback. This, at last, seems to get through to the girl, and she rushes off at once to demand of her father why he led her to believe that Demetrios was back on the seaways to Greece. Kronas has no real answer; Zaren’s answer, though unspoken, is plain enough.

Since this has turned into a pretty shitty deal all around, Antillia goes to the temple to pray. High Priest Azor (Edward Platt, from Cult of the Cobra and Black Zoo) now reveals himself as one of the good guys when he advises her that the gods to which she prays (and to which he, as high priest, is presumably beholden) are in fact false, and that if her prayers are to have any effect, they must be directed to the One True God who rules invisibly from the heavens above. And you thought Christianity didn’t get started until that Jesus guy showed up... Anyway, Azor arranges a meeting between Antillia and Demetrios, but it doesn’t go well, and may indeed be what precipitates the Greek’s subsequent trip to the House of Pai— I mean House of Fear. If I’m interpreting this section of the movie correctly, Antillia is one fickle little bitch, though, for no sooner has Dr. No-My-Name-Is-Absolutely-Not-Moreau begun gloating about what sort of creature he’s going to turn Demetrios into than a team of soldiers comes along to announce that the Greek has been granted the opportunity to win his freedom through a gladiatorial contest known as the Ordeal of Fire and Water. Demetrios kicks ass on both the fire and water portions of the exam, and is manumitted, much to the disgust of Zaren, the doctor, and Sonoy the Sinister Astrologer (Teenage Caveman’s Frank De Kova).

Okay, so we’ve now got a newly freed slave, an evil tyrant in the making, a princess to be rescued from a marriage she doesn’t want, and an entire Lost Continent’s worth of the downtrodden to release from bondage. Any guesses as to what sort of thing happens for the rest of the film? What if I told you that Zaren was planning to launch a war of conquest against the entire freakin’ world, to be effected by means of a death ray powered by the very same crystals that Demetrios was up until recently so busy mining? Yeah, well the only difference here is that Demetrios doesn’t have the brawn to go chucking any boulders around like a respectable sword-and-sandal hero. Instead, he has to make do with guile and trickery. First he sells his services as a cartographer to Zaren, filling him in on the geography of Mediterranean Europe, the one thing the Atlantians don’t seem to know anything about, but which they’re going to need to get a handle on soon if their war of global conquest is going to pan out properly. Then he manages to get himself appointed overseer of the crystal mines. He does this because kindly old Azor has told him what Zaren plans, and what the key ingredient of those plans is. He’s also told Demetrios about the geological catastrophe that threatens Atlantis with destruction from below. Demetrios figures he and his slave laborers can use their mining activities to help that destruction along, and it is on the very day that Zaren’s death-ray-packing troops were to have marched against Europe that the volcanoes and earthquakes begin, sinking Atlantis beneath the waves in an orgy of decade-old disaster footage recycled from Quo Vadis? and The Last Days of Pompeii. And inevitably, the only things that aren’t destroyed are Demetrios, Antillia, a handful of other slaves, and a squadron of boats to convey them back to their respective homes. Except for Antillia, that is. She gets to go to Attica and become Demetrios’s dutiful wife.

The first thing that hit me about Atlantis, the Lost Continent was the stunningly wooden acting. Seriously, it’s as though I’d stumbled upon a movie cast entirely with clones of Richard Kiel (though, of course, none of these actors are anywhere near that big— well, I suppose Demetrios’s opponent in the Ordeal of Fire and Water is). Anthony Hall gives the impression that he doesn’t really even speak English, and that his entire performance has simply been memorized by rote. John Dall as Zaren and Joyce Taylor as Antillia manage a little better than Hall, Taylor in that her performance hits two notes instead of one, and Dall in that his monotone is just a slight bit livelier. But as pitiful as the acting is, the writing is considerably worse. Gaps in the plot begin accumulating in the very first scene, when screenwriter Daniel Mainwaring neglects to mention what Antillia was doing floating around on a raft at the wrong end of the Mediterranean Sea in the first place. Characterization is baffling to say the least. I mean, we’re supposed to like the main characters, right? Isn’t that how it’s usually supposed to work? And yet Demetrios and Antillia both spend the entire film just begging to be slapped silly. Sure the Princess of Atlantis is pretty, but she’s nowhere near pretty enough to make any right-thinking man overlook her pettiness, selfishness, fickleness, or grating air of entitlement. The fact that Demetrios does overlook all those things— let alone the fact that he thinks nothing of ditching his aged father for what ends up being a good two and a half months without a word of explanation or even a goodbye, and does so in a way that deprives the old man of his only means of earning a living— makes him look like just as big a shit as Antillia. Why the hell should any of us care what happens to these two sorry fuckers? Then there’s the dialogue, which combines with the cast’s limitations to create an utter train-wreck of impossible lines delivered in an impossible manner. Do you suppose it could really be that Mainwaring seriously believed such utterances as “Even your words smell of fish!” or “I trust a man who favors money over honor” sounded anything at all like natural speech? Man, give me a Kirk Morris movie any day— at least the Italians seemed to understand at some level that they were making trash.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact