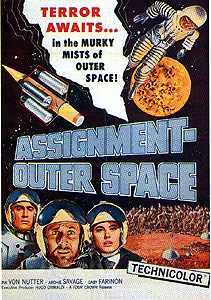

Assignment Outer Space/Space Men (1960/1961) -*Ĺ

Assignment Outer Space/Space Men (1960/1961) -*Ĺ

I guess we can file this one under ďEverybody Has to Start Somewhere.Ē I donít want to make Antonio Margheriti out to be some sort of unappreciated genius of science fiction cinema or anything, but his mature work in the genreó even the fairly dismal Planet on the Prowló exhibits a degree of style, enthusiasm, whimsy, and most of all personality that is simply nowhere to be found in Assignment Outer Space. In this film, his first as a solo director, Margheriti seems bound to a set of expectations that he is ill-suited to fulfill. Unlike every subsequent Italian space opera that Iíve ever seen, Assignment Outer Space wants very badly to be taken as seriously as, say, Destination Moon or Conquest of Space. Ennio De Cociniís script (written under the pseudonym Vassilij Petrovó given Stanslaw Lemís recent rise to international prominence, I wonder if the Russian-sounding name was a legitimacy scam along the same lines as the faux-British aliases so popular among Italian filmmakers working in Hammer-inspired Gothic horror) therefore has no place for such baroque embellishments as off-world clone factories, alien possession conspiracies, living rogue planets, or diabolical space yetis. Its hero is not particularly square-jawed, and he just barely qualifies as one-fisted. Even its sexy female astronaut is but a faint foreshadowing of her sisters to come. Yet a close examination reveals Assignment Outer Space to be no less half-assed or far-fetched than the Gamma 1 tetralogy, so all the striving after respectability accomplishes little but to deprive this movie of appeal that it might otherwise have offered.

That one-fisted man of inaction I mentioned is Ray Peterson (Rik Van Nutter, of Hard Times for Vampires and Colossus and the Huns), a journalist on the staff of the Interplanetary Chronicle of New York. On December 17th, 2116, Petersonís editor sends him out to Space Station ZX-34, in Galaxy M-12, to report on the station crewís investigation of anomalous infrared emissions in their sector of space. Here in act one, thatís a very long tripó long enough to require the Interplanetary Chronicle to book passage for Peterson aboard the sleeper ship BZ-88. Later on, though, De Cocini will forget all about that, and treat the return voyage to Earthís neighborhood as no more strenuous an undertaking than a jaunt to the corner bar. Heíll also forget about those infrared emissions, which is just as well, frankly. Trying to puzzle out the ramifications of general relativity for the 24-hour news cycle was making my brain sore.

Anyway, Al (Archie Savage, from Virgin of the Jungle and the Franco-Italian The Thief of Baghdad) and Archie (Alain Dijon, of The Invisible Dr. Mabuse and The Testament of Dr. Mabuse), the pilot and navigator respectively of the BZ-88, give Ray a raft of shit about his inexperience with travel in deep space, and about his fundamental superfluity to any of the work that will go on either aboard the ship or on the space station, but their prickly attitudes are mostly a put-on. The same cannot be said of George (David Montressor), the commander of Station ZX-34, however. George is openly resentful of Petersonís presence, regarding the reporter as at best a toddler in need of babysitting, and at worst a spy in need of vigilant policing. Indeed, the commanderís sullen suspiciousness is not allayed even when Peterson saves the life of Crewmember Y-13ó also known as Georgeís girlfriend, Lucy (Gaby Farinon, of Blood and Roses)ó during the extravehicular excursion necessary for refueling the BZ-88. For one thing, Peterson wasnít supposed to be outside the station at all, and he certainly didnít have Georgeís permission to film the refueling operations. And for another, while shoving Lucy out of the path of that meteor, Ray propelled himself straight into the fuel line, dislodging it from its port in the shipís boost stage and spilling 500 gallons of neohydrozene propellant before the stationís crew could shut off the pumps. While chewing the reporter out afterwards, George directly states that he considers the orderly functioning of his space station and the conservation of its resources to be of far greater importance than a single human life.

Mind you, Peterson doesnít know yet that Crewmember Y-13 is Station ZX-34ís only woman, and he certainly has no idea about her relationship with the commander. After all, one person in a space suit looks more or less exactly like any other. Their proper meeting shortly after the rescue is practically the Platonic Ideal of the ďButÖ youíre a girl!Ē scenes that were so beloved by the writers of crappy sci-fi movies during the middle of the last century. For one thing, Gaby Farinon and Rik Van Nutter fail as completely to establish the chemistry between Lucy and Ray that will supposedly be so important later on as any pair of actors Iíve ever seen. And better yet, Peterson actually says, ďButÖ youíre a girl!Ē the first time he sees Lucy without her space suit. Itís honestly sort of charming to see a movie commit to sucking like that.

Now George has been acting from the word go as if he were hiding something nefarious out there on Station ZX-34, and with his unapologetically cavalier attitude toward the lives of his crew, youíre probably expecting Assignment Outer Spaceís plot (once it finally deigns to put in an appearance) to concern Peterson discovering the commanderís secret and using his position with the Interplanetary Chronicle to bring him to justice. That might even have been where De Cocini thought the story was headed, too, when he started writing. If so, the premise held his attention no better than that radiation Ray was sent up to write about, for George now receives orders from the High Command to embark for Mars aboard the BZ-88. At first, the commander plans on leaving both Ray and Lucy behind on the station, but that doesnít last very long. On the one hand, Peterson pulls some strings via the Chronicle to get himself attached to Georgeís hush-hush mission, and on the other, Lucy effortlessly convinces her boss/ boyfriend that a trained navigator (which is to say, Lucy) is the last person the commander ought to be cutting from the crew in order to make room for the reporter.

So whatís this mission to Mars all about? Well, the rocketship A-2 has suffered some sort of computer malfunction on its voyage home from someplace or other. The crew are dead in their hibernation chambers, the autopilot isnít accepting outside commands, and unless something happens to knock it off its present course, the ship will follow its programming until it falls into orbit around Earth. Normally that would be exactly what the High Command wants, but the A-2 was a testbed for a new type of propulsion based on photonic energy (or maybe protonic energyó the cast is sharply divided on the subject, and a few of them are even adamant that the A-2ís engines use potonic energy), and the engines are behaving even worse than the computer. Somehow, the photonic energy is feeding back through the shipís shields, projecting a curtain of irresistible heat around the A-2 at a radius of 5000 miles. The Earthís radius, meanwhile, is a bit less than 4000 miles, and the A-2ís computer is programmed to take up its orbit 1500 miles above the surface. It wonít take the A-2 very many orbits to bake the entire planet, so obviously somebody had better intercept the wayward ship and either destroy it or send it off someplace else where it wonít bother anyone. You might ask what the hell kind of sense it makes to entrust this urgent undertaking to a ship that is currently orbiting a starbase in another fucking galaxy, but itís probably better not to.

George and his crew get a small taste of the A-2ís power when they encounter the Moon-based rocket MS-13 in the vicinity of Mars. That ship was barely nicked by the A-2ís shields, and itís now dead in space with blown-up fuel tanks, a melted boost stage, and a dead engineer. The MS-13 crash-lands on Phobos before the BZ-88 can intervene, but the latter vessel does manage to rescue one survivor afterwards. Thereís no sign of the A-2 anywhere near Mars now, so the BZ-88 hurries ahead to Venus instead, where the crew can assist the personnel of a military outpost equipped with an arsenal of nuclear missiles. Naturally, the missiles fare no better against the A-2ís bubble of death than the Moon rocket, but Al notices something interesting about the fate that befalls the second one fired. It was able to approach nearly twice as close to its target before being destroyed, which suggests that the A-2ís heat field is discontinuous. An old warship, the TS-13, is part of the Venus garrison, and Al proposes to take it up to a position from which he might be able to fire a nuclear warhead straight through the gap.

I have two favorite moments in Assignment Outer Space, both of them instances in which something has gone catastrophically wrong, but it isnít initially apparent exactly what or how. The first comes when the MS-13 smashes into the surface of Phobos. Itís immediately obvious that this is an extraordinarily ill-edited scene, and that a disembodied stock-footage explosion has been tossed in to represent the spaceshipís destruction. More importantly, though, thereís something ineffably off about the explosion itself. Decadesí worth of viewers had no practical way to solve this maddening visual mystery, but thanks to home video, you have only to pause the film at the 31:23 mark to see exactly whatís the matter. Yes, that is indeed a Ď56 Chevy in the foreground there, together with a house and a rank of telephone poles on the far side of the explosion. I donít know where the hell Margheriti found those few frames of something blowing up in the middle of a raggedy city street, but thereís no way he could have chosen a less appropriate bit of film to represent a crippled rocketship crashing on one of the moons of Mars! The other offers a more cerebral sort of entertainment, for it serves as the final confirmation that Ennio De Cocini has simply lost all track of what heíd written previously. Itís supposed to be a moving moment of heroism, as Georgeís first officer, Sullivan (Franco Fantasia, from The Giant of Marathon and The Mountain of the Cannibal God), back on Station ZX-34 goes down with theÖ well, I guess it isnít a ship, really, but you know what I mean. As the A-2 approaches behind its all-destroying wall of photonic heat, Sullivan courageously mans his command post so as to coordinate the escape of as many of the crew as possible, although he himself is doomed by doing so. Hereís the thing, thoughÖ The A-2 has just passed Venus on its way around the sun, and is now entering the home stretch to Earth, right? And Station ZX-34 is in Galaxy M-12, right? So how exactly does the interstellar fireship come within 5000 miles of the station on its final approach to Earth when ZX-34 and the homeworld ought to be untold millions of light years apart?

You can easily see, then, that Assignment Outer Space is a singularly flaccid example of hard sci-fi, scarcely deserving of the earnest gravity with which Margheriti has attempted to invest it. Itís both dumb and dull on the whole, despite a few impressively forward-looking touches like treating a black man in a position of respect and authority as if that were a completely ordinary and unremarkable state of affairs. About the best thing I can say for this movie in its intended role is to note that it marked the debut of some lovely spaceship models that would become as familiar as old friends in Italian sci-fi films throughout the rest of the 60ís. Most notably, fans of the Gamma 1 series will recognize the BZ-88 as being just a paintjob away from the United Democracies Space Command flagship, and I believe Station ZX-34 enjoyed a second career as one of the Delta-series orbital bases in those movies as well. It isnít much to go on for ordinary, non-obsessed viewers, but like I said at the beginning of the review, everybody has to start somewhere.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact